Bailey Hill, YRK Environmental Justice Advocate

My work with YRK is focused on identifying, supporting, and advocating for communities throughout the Yadkin River Basin that face disproportionate impacts from environmental stressors, such as water pollution and creek erosion. Due to the nature of my role as an EJ Advocate, it is important to seek guidance from those who have experience in grassroots activism and community engagement. One organization we look to for EJ support is the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network (NCEJN), which has been influential in helping communities organize and stand up to polluting industries across the state. YRK first partnered with NCEJN a few years ago when residents of West Badin organized to advocate for pollution clean-up at the former Alcoa aluminum plant. As our advocacy for clean-up in West Badin continues, we are working to build a stronger relationship with NCEJN to increase our efforts in that community as well as others throughout the basin.

On the morning of Friday, October 14th, Grace and I began our journey to the town of Whitakers to attend NCEJN’s 23rd Annual Environmental Justice Summit. Upon arriving at our destination, we were greeted by seemingly endless acres of cotton, tobacco, and soybeans. Nestled among the crops lay the conference center where we would spend our weekend “remembering, recovering, resting, and reimagining” with a hundred environmental justice advocates from across the state.

This conference center is home to the nonprofit organization Franklinton Center at Bricks, whose mission is to “provide a nurturing home to local, national, and global programs and organizations seeking liberation.” In 1895, Mrs. Joseph K. Brick funded the establishment of Brick School for Black children on this land which was once a plantation. The school earned accreditation and became a junior college in 1926. The legacy of Mrs. Brick remains through the preservation of historic homes and buildings throughout the campus.

Teachers Cottage: This two-story cottage was built in 1895; and served as a home for teachers who worked at the Joseph Keasby Brick Agricultural, Industrial and Normal School. Photo courtesy of Franklinton Center at Bricks

Inborden House: This two-story cottage was built in 1895; and was home to the family of Mr. Thomas Sewell Inborden, Principal of the Joseph Keasby Brick Agricultural, Industrial and Normal School.

Photo courtesy of Franklinton Center at Bricks

Model School House: Built as part of the Brick Tri-County Public School in the style of the Rosenwald Schools by Harry Mills.

Photo courtesy of Franklinton Center at Bricks

NCEJN has hosted annual meetings at Franklinton Center at Bricks since their first gathering in 1997. Those who attended past summits said that this year’s felt different. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic NCEJN did not host a summit during the past 2 years, so the 2022 gathering was designed to feel like a family reunion. Friday’s events were held outside at the “Area of Remembrance.” A sign marked “whipping post and Magnolia tree” stood in front of the area as a reminder that for generations this land was a place of trauma and enslavement.

Area of Remembrance: Chris Hawn, Co-Director of Research and Education for NCEJN, welcomes everyone to the reunion.

We gathered around the Magnolia tree to reflect on the significance of this conference center as a place of liberation and healing–something that the environmental justice movement as a whole has embodied since its inception in the late 1980s. In the spirit of resistance, Friday evening ended with fireside retellings of social justice victories involving the work of NCEJN, Black Workers for Justice, and other personal anecdotes from EJ advocates across NC. Naeema Muhammad, Senior Advisor and co-founder of NCEJN, reflected on her early days of EJ activism and how the movement involves all areas of justice–social, labor, and environmental.

Bailey Hill (left), YRK’s Environmental Justice Advocate and Grace Fuchs (right), YRK’s Riverkeeper Assistant

Saturday’s sessions were held at Memorial Hall, the oldest functional building at the conference center. Zulayka Santiago, co-chair of the NCEJN Board, posed a question to all the attendants: How do we be in right relationship with the more than human world? Environmental justice as a movement calls into question our current treatment of the earth and our relationship to other living beings within it. It is necessary for us as individuals and for humanity as a collective to reevaluate our interactions with nature. As we advocate for environmental justice and the liberation of those who are most harmed by polluting industries and capital-centered corporations, we must also “intellectually and emotionally” plan for the future. Rania Masri, Co-Director of Organizing and Policy at NCEJN, challenged us to develop strategies for how we will interact with “the land” post-liberation.

The keynote speaker for Saturday’s session was Pallav Das, the co-founder of Kalpavriksh Environmental Action Group in India. In building upon the foundation set by Santiago and Masri, Das presented alternative ways in which we as humans might interact with the environment. This didn’t involve suggestions to live “off the grid” or boycot all manufactured products, but rather, to challenge the view of nature as a commodity. Violence against nature, communities, cultures, and individuals stems from an anthropocentric belief in which human beings are the central, most important element of existence. From this view, all other beings in nature are only valuable in their ability to serve humans.

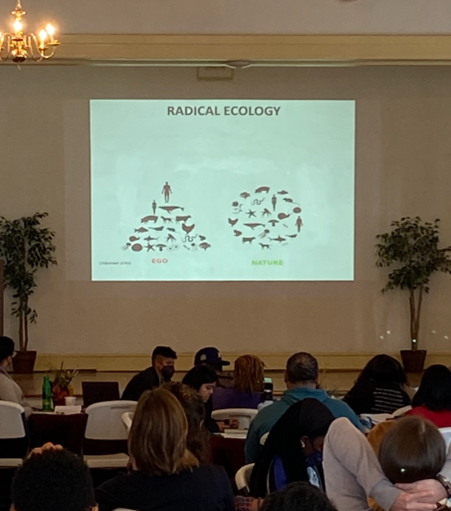

Das outlined the alternative to anthropocentric belief→ radical ecology, in which all beings are viewed as part of the collective whole of nature. The Latin meaning of “radical” means “root.” What is assumed to be a bizarre or outlandish way of thinking is actually a sentiment rooted in respect for the natural world and respect for one another.

Pallav Das speaking to NCEJN Summit attendant inside Memorial Hall

The Summit was officially brought to a close on Saturday afternoon with a ritual that began at the first NCEJN Summit in 1997. All attendants were asked to stand hand-in-hand with one another to form a circle around the room. Beginning with Naeema Muhammad, each attendant proclaimed: I am a link in the chain, and the link in the chain will not break here! This statement of solidarity was spoken individually by each person in the room to ensure that everyone understood the personal commitment being made. The fight for environmental justice requires dedication and momentum. Each link in “the chain” of advocates must be tightly connected in order to withstand the tension of standing up against polluters who threaten the health and well being of our most vulnerable communities.

Bailey (left) and Grace (right) outside Memorial Hall